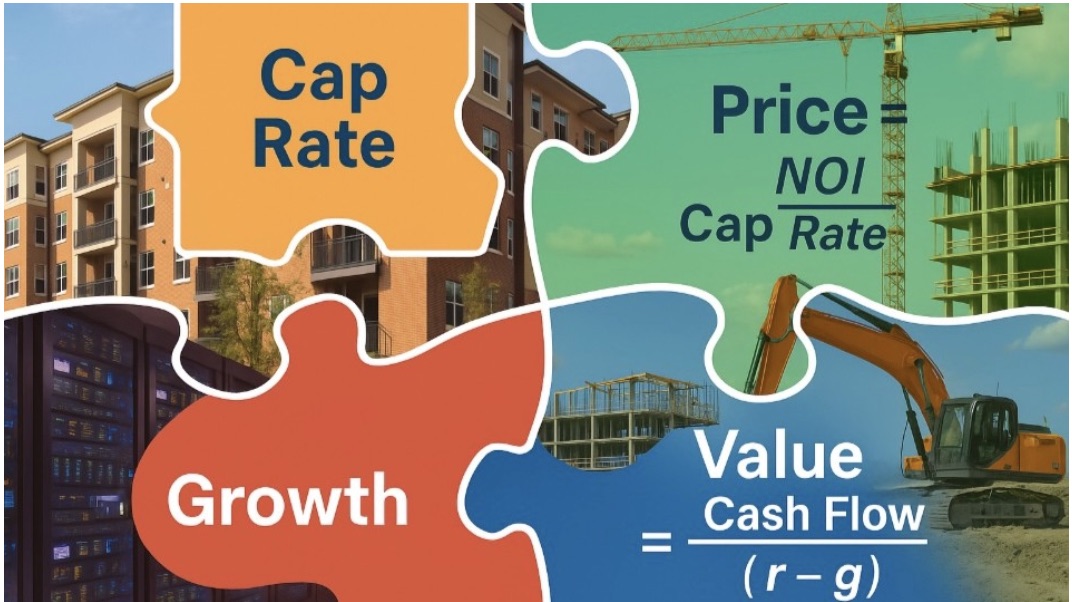

Professor Aswath Damodaran, the highly regarded (and brilliant) professor who teaches corporate finance and valuation at NYU, has written that for many classes of real estate growth is irrelevant since investments of capital in those assets almost never yield a return in excess of the cost of capital. Given all of this it is fair to ask: “What the heck is going on?” What role, if any, does growth play in defining or using cap rates. The source of the trouble is pretty clear—two formulas that look almost identical:In corporate finance there is the formula for a growing perpetuity: Value = Cash Flow / (r - g),where r is the discount rate and g is the projected growth in cash flow.

In real estate there is the ubiquitous cap rate: Price = NOI / Cap RateWhile cash flow is not technically the same thing as NOI, you could be forgiven for concluding that they are saying essentially the same thing and that cap rate = (r-g). In fact, neither statement is correct. The Fundamental Difference In corporate finance the perpetuity formula is a critical valuation tool used in discounted cash flow analysis (DCF).

It is used after the explicit forecast period and typically has an outsized impact on valuation. It is anchored in discount rates and growth. The cap rate is not about valuation.

It is just a ratio — todayʼs NOI divided by todayʼs price. It is not intended to be an anchor in a valuation model. Moreover, keep in mind that while in corporate finance it is assumed that corporations have infinite lives, in real estate we are usually modeling a specific hold period,e.g.5, 7 or 10 years.

A perpetuity model isipso factoa questionable analytical tool. But hold on—it gets worse! The P/E Ratio—More Confusion Cap rates also resemble the P/E ratio flipped upside down (E/P).

But unlike P/E ratios, which reflect growth and return expectations, cap rates are nothing more than NOI/Price, with no growth assumptions embedded in the formula. When two companies in the same industry, with similar characteristics are trading at different P/E multiples, the answer can often be found in disparate assumptions about growth. You would be foolish to try to use cap rates that way.

Cap Rates and IRR As long as we are piling on, it is worth noting that sometimes someone will offer up a rough, very back of the envelope formula indicating that: Going in cap rate + projected NOI growth rate = unlevered IRR. This always comes with lots of warnings that this applies only in very narrow circumstances involving core, unlevered properties with long expected hold periods and modest inflation-linked growth, where the exit and going-in cap rates are identical. So where does all of this leave us?

What is the relationship between cap rates and growth? Regardless of how similar the perpetuity and cap rate formulas appear, it is best to remember that cap rates are intended only as a description of a real estate assetʼs current price and its NOI (forward, unlevered, pre- tax, hopefully remembering that NOI is calculated before capex and leasing expenses). Growth isnot specifically modeledinto cap rates.

Having said that, it is not quite that clean and simple. The market often does implicitly bake insomeview of growth in cap rates — but only in a very rough, non-mathematical way. For stabilized assets, particularly multifamily, the market often assumes that NOI growth ≈ inflation and that it washes out against rising expenses and capex.

Thus, “g” is often treated as small or irrelevant in practice, and the cap rate formula reduces to a no-growth perpetuity. Of course, if you are in a high-growth niche,e.g.,sunbelt multifamily, logistics, data centers, etc. different assumptions will govern.

Moreover, Class A multifamily in Austin might trade at 4.5% while suburban office in the Midwest trades at 8%. That spread encodes differing assumptions about growth and risk. Fair enough.

If you want to make specific assumptions about growth and determine if it matters financially you need to leave the cap rate world and move into the world of DCF. Once there, the most important point to keep in mind is that value is created or increased only if the return on (re)invested capital is greater than the cost of capital. If ROIC = WACC then growth is adding scale but not value.

Practically, this means that in the world of stabilized multifamily it is hard for growth to increase value absent repositioning (e.g.Class B to Class A), densification or adding new uses for underutilized sq. footage. Where Cap Rates and Valuation Merge There is one area where valuations in real estate do rely heavily on cap rates.

Assume you are modeling a development project. In order to project returns over your expected hold period you need topro forma the sale of the asset. The accepted way to do that is to apply some cap rate to the assetʼs NOI in the projected year of disposition.

If you were valuing a company and applied a P/E ratio after the explicit forecast period to close out your DCF model, you would be accused of laziness and told to try harder. But what matters in real estate is the price that the market will be willing to pay for the asset, not some value that comes out of a perpetuity model. Of course, itʼs guesswork—guesswork that can have a huge impact on the projected value.

If you find that problematic —get over it. Thatʼs the way the world works.